Realizing His Path

In 1961, Thay was offered a Fulbright Scholarship to broaden his experience and scholarship, and travelled to the U.S. to study Comparative Religion at Princeton Theological Seminary, from 1961-62.

In 1961, Thay was offered a Fulbright Scholarship to broaden his experience and scholarship, and travelled to the U.S. to study Comparative Religion at Princeton Theological Seminary, from 1961-62.

It was in Princeton that Thay experienced his first autumn, his first snows, and the fresh beauties of spring following winter. In the peace and calm, his insights had a chance to ripen, “It was there that I truly tasted, for the first time, the peace of dwelling happily in the present moment” (the ancient Buddhist teaching of dṛṣṭadharmasukhavihāra).

Thay later reflected on these formative years in the U.S.: “I grew up in Vietnam. I became a monk in Vietnam. I learned and practiced Buddhism in Vietnam. And before coming to the West, I taught several generations of Buddhist students in Vietnam. But I can say now that it was in the West that I realized my path.”

In summer 1962, while guiding young people at Camp Ockanickon in Medford, New Jersey, Thay captured these “first blossoms of awakening” in A Rose for Your Pocket. It was a simple, lyrical little book in celebration of mothers, inspiring the reader to cherish what they have right now in the present moment.

Thay sent A Rose for Your Pocket to Co Nhien — one of his student “cedars” in Vietnam — who arranged for its publication right away. It was first published in Vietnamese in the Buddhist magazine Lotus in 1962, under his own name, with the title Seeing Your Mother Deeply (Nhìn kỹ Mẹ). It was subsequently one of the first books to be printed by La Boi publishing house in 1964. In 1965, the professional singer Pham The My performed it as a modern Vietnamese song.

The information in this section is drawn from Thich Nhat Hanh’s books Fragrant Palm Leaves (1999) and At Home in the World (2016).

The spirit and approach of A Rose Your Pocket broke entirely new ground in Buddhist writing, and crystallised Thay’s distinctive writing style. There had never before been a book in Vietnamese which so lyrically applied Buddhist insights into a spiritual perspective on daily life, and it rapidly became a bestseller. Written in natural, poetic language that even children could understand, A Rose for Your Pocket didn’t have the form of a Buddhist teaching, but was in essence a guided meditation to help the reader to touch the wonder of their mother’s presence in the here and now.

For the first time, a Buddhist monk was showing how meditative awareness could be a bright and gentle energy. The reader could touch the fruit of meditation without having to turn their heart and mind into a battlefield, fighting anger, grief, or craving. With its publication Thay, who hitherto had been known as a poet, editor and Buddhist scholar, became known for his deep and accessible Buddhism. On Mother’s Day that year, Thay’s students organised a “Rose Festival” to celebrate motherhood, based on the book.

The “cedars” organized for 200 handwritten copies to be prepared for the first Rose Ceremony. A red rose or a white rose was attached to each copy depending on whether the receiver’s mother was alive or deceased. The festival soon became an annual tradition celebrated across Vietnam, and it is today an integral part of Buddhist culture in the country. The book has sold over a million copies, and can be found in every Buddhist home. Its fresh and intimate tone that so appealed to Vietnamese Buddhists created a new genre in modern Buddhist writing, adopted in both East and West.

After completing his year at Princeton, Thay stayed on in the U.S. and continued his research at Columbia University from 1962-63). There, he made the most of the extensive Buddhist collection in the Butler Library, and benefited from the mentorship of the distinguished Professor Anton Zigmund-Cerbu and encountered the work of contemporary theologians. Professor Zigmund-Cerbu was a specialist in Buddhism, and was said to have mastered 40 languages. Ten years older than Thay, Prof. Cerbu passed away after undergoing heart surgery just a few months after Thay returned to Vietnam.

Half a century later, in 2017, Columbia’s Union Theological Seminary would create a “Thich Nhat Hanh Master’s Program for Engaged Buddhism” in his honor.

In November and December 1962, Thay experienced a series of deepening spiritual breakthroughs. He had been profoundly moved by the writings of Dietrich Bonhoeffer — a German pastor and theologian, and a bold, outspoken critic of the Nazi regime, who was imprisoned and later executed in 1945.

Reading Bonhoeffer’s account of his decision to return home to Germany from the U.S., even though it put his life at risk, Thay was struck by his description of his final days in prison, “…I was awakened to the starry sky that dwells in each of us. I felt a surge of joy, accompanied by the faith that I could endure even greater suffering than I had thought possible.

Bonhoeffer was the drop that made my cup overflow, the last link in a long chain, the breeze that nudged the ripened fruit to fall. After experiencing such a night, I will never complain about life again. […] All feelings, passions, and sufferings revealed themselves as wonders, yet I remained grounded in my body. Some people might call such an experience ‘religious,’ but what I felt was totally and utterly human. I knew in that moment that there was no enlightenment outside of my own mind and the cells of my body. Life is miraculous, even in its suffering. Without suffering, life would not be possible.”

The story of Thay’s interest in Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s writings is excerpted from Thay’s book Fragrant Palm Leaves (1999). Bonhoeffer considered taking refuge in the U.S., but soon realised: “I will have no right to participate in the reconstruction of Christian life in Germany after the war if I do not share the trials of this time with my people.” He was also critical of the Church’s response to the situation: “the Church was silent when it should have cried out, because the blood of the innocent was crying aloud to heaven.” Quoted in Franklin Sherman, “Dietrich Bonhoeffer,” in Encyclopaedia Britannica (2019).

It was in 1963, during the annual spring Vesak festival, that the Diem regime’s suppression of Buddhists dramatically escalated. He submitted his documents on 8 October, 1963, the day of the U.N. debate on President Ngo Dinh Diem’s suppression of the Buddhists.

In America, Thay found himself becoming an active spokesman for the Buddhist peace movement back home. He gave talks and media interviews, and submitted a report to the United Nations on the human rights violations. Thay learned of the self-immolation of the senior monk, Venerable Thich Quang Duc from the article “Man Sets Himself Afire” in the July 1, 1969 issue of The New York Times. The Most Venerable Thich Quang Duc was 73 years old.

Thay knew him well and had stayed with him in Nha Trang and Saigon. Thay later explained: “When you commit suicide, [it’s because] you are in despair, you can no longer bear to live. But Venerable Quang Duc was not like that. He wanted to live. He wanted his friends and other living beings to live; he loved being alive. But he was free enough to offer his body in order to get the message across that we are suffering, we need your help.”

Before long, Thay got news of the self-immolation of more monks and nuns — in August 1963: Br. Nguyen Huong; Br. Thanh Tue; Sr. Dieu Quang; and Br. Tieu Dieu. His poem, “The Fire That Consumes My Brother,” from Thay’s book Call Me By My True Names (1993) captured his agony and his firm resolve to continue to work for peace.

“…The fire that burns you burns my flesh with such pain, that all my tears are not

enough to cool your sacred soul. Deeply wounded, I remain here keeping your hopes and promises for the young. I will not betray you– are you listening? I remain here because your very heart is now my own.”

Thay’s description of the Most Venerable Thich Quang Duc is excerpted from his 7 June, 2002 Plum Village Dharma Talk.

In August 1963, over a thousand Buddhist monks were arrested, and hundreds more “disappeared.” Thay submitted documents concerning the persecutions to the United Nations, called a press conference, and began fasting to pray that the U.N. would send a fact-finding delegation to Vietnam.

After the Diem regime fell in November 1963, Thay received a cable from Thich Tri Quang, one of the leading monks in Vietnam and a leading figure in the Buddhist hierarchy, calling him back to Saigon to help once more in efforts to support Vietnamese Buddhism and galvanize its response to the worsening situation. Thich Tri Quang wrote Thay a telegram, and then a letter saying, “I am exhausted and at my wit’s end. Please come back and help.”

The account of monks being arrested and “disappeared” is drawn from Sisten Chan Khong’s book, Learning True Love (Rev. 2007).

Returning to Vietnam in January 1964, Thay entered into a leadership role in the Buddhist movement for peace and social action. This nonviolent resistance movement was called the “Third Force” in Vietnamese politics at the time.

He met with Buddhist leaders and students to hear their reports. He offered two concrete proposals for the young social workers and activists: first, to dedicate one full day every week to spend time together at the Bamboo Forest Temple, to calm body and mind and nourish their aspiration; second, to invest in establishing pilot villages for rural reconstruction and development.

In addition, Thay made three proposals for the Unified Buddhist Congregation to address the violence and discord:

The following years were a period of intense activity and engagement as he galvanized the young generation through his teaching, writings, community-building, and vision for social service.

The great flood of November 1964 in central Vietnam swept away homes and took thousands of lives. Victims in the conflict zones were the most vulnerable because no one dared to bring them aid. Thay, Brother Nhat Tri and Phuong organized boats and went up the Thu Bon River between the lines of fire to distribute aid in the Đức Dục area of Quang Nam Province. They encountered children bleeding from gunfire wounds, malnourished young men, and fathers whose entire families had been swept away. In a gesture of compassion and solidarity, Thay cut his finger and let the blood fall into the river to pray for all those who had perished.

By June 1965 the military had seized control of government; violence and oppression escalated. “Civil liberties were restricted, political opponents—denounced as neutralists or pro-communists—were imprisoned, and political parties were allowed to operate only if they did not openly criticize government policy.”

Guerrilla fighters continued their struggle. Thay continued to write bold and stark peace poetry, capturing the agony of the people. His collection, Palms Joined in Prayer for the White Dove to Appear, was published in 1965. Over 3,000 copies were sold in the first two weeks. Before long, the poems were denounced on radio as “anti-war poetry” by both sides, endangering his safety. Thay himself never considered the poems “anti-war” poetry, as he said they were not ‘anti’ anything; they were simply “peace poems”. Nonetheless, they circulated widely underground and became popular peace songs, sung in the streets and at student meetings.

The information in this section is drawn from Thich Nhat Hanh’s books Call Me By My True Names (1999) and Chắp Tay Nguyện Cầu Cho Bồ Câu Trắng Hiện (1965) as well as “The two Vietnams (1954–65),” by William S. Turley, Neil L. Jamieson and Others, Encyclopaedia Britannica.

In 1965, afraid that the communists were gaining ground, U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson sent the first combat troops to Vietnam.

By the summer of 1965, there were over 125,000 U.S. soldiers on the ground in Vietnam. Thay and other leading intellectuals in Vietnam decided they needed the help of high-profile spiritual and humanitarian leaders to shift public opinion in the West. In June 1965, Thay wrote to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., while Ho Huu Tuong wrote to Jean Paul Sartres; Tam Ich wrote to André Malraux; Bui Giang wrote to René Char; and Pham Cong Thien wrote to Henry Miller. These letters were published in the book Dialogue (1965), published in English by La Boi Press.

In the West at the time, there was a lot of misunderstanding about the shocking images of self-immolations. Thay’s letter to Dr. King explained the compassion behind the Buddhist immolations, and explained that “Nobody here wants the war. What is the war for, then? And whose is the war? […] I am sure that since you have been engaged in one of the hardest struggles for equality and human rights, you are among those who understand fully, and who share with all their hearts, the indescribable suffering of the Vietnamese people. The world’s greatest humanists would not remain silent. You yourself can not remain silent.”

By the time Thay and Dr. King met a year later, in Chicago, Dr. King had joined the International Committee of Conscience on Vietnam.

In September 1965, Thay and his colleagues formally founded the School of Youth for Social Service (SYSS) [Thanh Niên Phụng Sự Xã Hội (TNHSXH) in Vietnamese]. Rallying thousands of student volunteers, the SYSS provided a formal structure for the engaged social action that Thay and the “thirteen cedars” and colleagues were pioneering. They created a politically-neutral grassroots relief organization to train young people in practical skills and spiritual resilience, and send them out to bombed villages and undeveloped communities, to set up schools and medical centers, resettle homeless families, and organize agricultural cooperatives.

In SYSS in Vietnamese is Thanh Niên Phụng Sự Xã Hội (TNHSXH). See a brochure of their activities.

The students, inspired by the ideal of service, like Peace Corps members in the West, helped full-time as volunteers in the villages, and had no income. But it was extremely difficult to conduct their social work in the context of suspicion, hatred, fear and violence. Danger could come from any side, at any moment. Thay’s friends were arrested, social workers were threatened, and weapons were always close to hand.

“If you don’t have a spiritual practice, you can’t survive,” Thay explained. And so “Engaged Buddhism is born in such a difficult situation, in which you want to maintain your practice while responding to the suffering. You seek the way to do walking meditation right there, in the place where people are still running under the bombs. And you learn how to practice mindful breathing while helping care for a child who has been wounded by bullets or bombs.”

The information in this section is drawn from Thich Nhat Hanh’s book At Home in the World (2016), a 29 August, 2013 Q&A at Blue Cliff Monastery, and a 21 June, 2009 Dharma Talk in Plum Village.

Their own suffering and difficulties acted as their greatest teacher. “The hardest thing is not to lose hope, not to give in to despair,” said Thay. “In a situation of utmost suffering like that, we [have to] practice in such a way that we preserve our hope and our compassion.”

It was during this time that one of the villages they had been helping near the Demilitarized Zone, was bombed. They rebuilt it. When it was bombed a second time, the social workers asked Thay if they should rebuild it, and he said, “Yes.” When it was bombed a third time, he reflected for some time and then replied, “Yes.”

As Thay later explained, “It did not seem that there was any hope of an end, because the war had been dragging on for so long. I had to practice a lot of mindful breathing and coming back to myself. I have to confess I did not have a lot of hope at this time, but if I’d had no hope, it would have been devastating for these young people. I had to practice deeply and nourish the little hope I had inside so I could be a refuge for them.”

The information for this section is drawn from Thay’s book At Home in the World (2016).

In February 1966 Thay took a step further in building community and established the Order of Interbeing (Dòng Tu Tiếp Hiện in Vietnamese), a new order based on the traditional Buddhist bodhisattva precepts, expressed with an innovative vision of a modern, engaged Buddhism.

It embodied Thay’s teaching of “not taking sides in a conflict,” and emphasised non-attachment to views, and freedom from all ideologies. For Thay these precepts were “a direct answer to war, a direct answer to dogmatism, where everyone is ready to kill and die for their beliefs.”

Today there are over 3,000 members of the Order of Interbeing around the world.

During a talk on 7 April, 2008 in Hanoi, Thay discussed first version of The Fourteen Mindfulness Trainings:

As Thay wrote, “The Vietnam War was, first and foremost, an ideological struggle. To ensure our people’s survival, we had to overcome both communist and anticommunist fanaticism, and maintain the strictest neutrality. Buddhists tried their best to speak for all the people and not take sides, but we were condemned as ‘pro-communist neutralists.’

Both warring parties claimed to speak for what the people really wanted, but the North Vietnamese spoke for the communist bloc and the South Vietnamese spoke for the capitalist bloc. The Buddhists only wanted to create a vehicle for the people to be heard — and the people only wanted peace, not a “victory” by either side.”

But, he said, “...the sound of the planes and bombs was too loud. The people of the world could not hear us. So I decided to go to America and call for a cessation of the violence.”

The information in this section is drawn from Thay’s book Love in Action (1993) and from a Public Talk at the Riverside Church, NYC, on 25 September, 2001.

In spring 1966, Thay was invited by Dr. George Kahin of Cornell University to travel to the U.S. to give a lecture series on the situation in Vietnam at the university’s Department of Politics, South-East Asia. Dr. Kahin was from Cornell’s Department of Politics, South-East Asia, and the trip was sponsored by Cornell’s Inter-University Team.

Alfred Hassler, Executive Secretary of the Fellowship of Reconciliation (the prominent international interfaith organization for peace and justice) then invited Thay to tour universities and churches across the U.S., Europe, Asia, and Australia, to speak out for peace. Mr. Hassler had visited Vietnam the previous year and met Thay at Van Hanh University that summer.

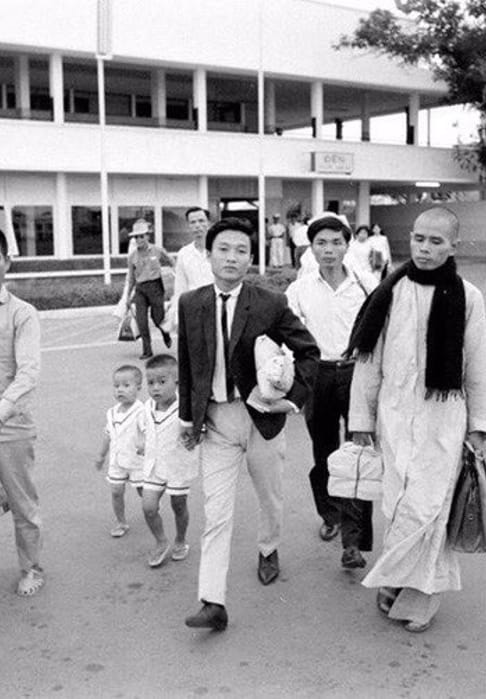

Thay left Vietnam on May 11th, 1966 for the short trip. But it would be 39 years before he could return home. On the eve of his departure, his teacher formally transmitted him the Dharma Lamp. In this important Buddhist ceremony, Thay formally became a Dharma Teacher of the Lieu Quan Dharma Line, in the 42nd generation of the Linji School. Thay’s teacher also expressed his wish to transmit the abbotship of Tu Hieu Temple to Thay in the future.

When he left Vietnam, Thay was a leading figure in the Buddhist peace and social work movement, had published ten books, and was one of the country’s most popular poets.

Thay’s 1966 speaking tour saw him visit 19 countries, calling for peace and describing the aspirations and the agony of the voiceless masses of the Vietnamese people. Journalist James A. Wechsler — in an article titled in the May 18, 1966 edition of the New York Post — described the impression Thay made on him, just a few days after arriving in the U.S.:

He is a tiny, slender, robed figure; his eyes are alternately sad and animated; his tones are modest and moving. In the American vernacular, there is probably a price on his head in Gen. Ky’s Saigon. [... H]e spoke in the international language of the scholar who finds himself thrust into the drama of history, crying not for peace at any price, but for an end to madness. [...] When asked about ‘freedom’ and ‘democracy,’ he will ask, “What is the use of freedom and democracy if you are not alive?” [...] Listening to this frail, earnest figure, one wondered whether the State Dept. would permit President Johnson direct exposure to him.

In the U.S., Thay met the high-profile peace activists and Christian mystics Father Daniel Berrigan and Father Thomas Merton, as well as leading politicians including Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara and Senator Edward Kennedy.

In the book Learning to Love: The Journals of Thomas Merton, vol. 6 (1997), Thomas Merton recorded in his journal after meeting Thay for the first time, “He is first of all a true monk; very quiet, gentle, modest, humble, and you can see his Zen has worked.”

“We talked about human rights, peace, nonviolence,” recalled Thay.

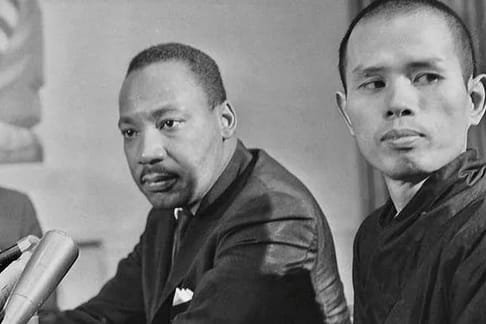

That year, Thay also met Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., with whom he had begun corresponding a year earlier. “We talked about human rights, peace, nonviolence,” recalled Thay. “What we were doing was very similar — building community, blending the seeds of wisdom, compassion, and nonviolence.” On May 31st, 1966, they held a press conference in Chicago at the Sheraton Hotel, one of the first occasions Dr. King spoke out publicly against the war in Vietnam.

In a joint statement, they compared the civil rights protestors and the self-immolations in Vietnam, “We believe that the Buddhists who have sacrificed themselves, like the martyrs of the civil rights movement, do not aim at the injury of the oppressors, but only at changing their policies. The enemies of those struggling for freedom and democracy are not men. They are discrimination, dictatorship, greed, hatred, and violence, which lie within the hearts of man. These are the real enemies of man — not man himself.”

According to FBI reports, earlier in the day, Thay had participated in an ecumenical peace service at Rockefeller Chapel on the Chicago University campus, attended by many senior clergy.

The 1966 trip was an intense time. The day after his conference with Dr. King in Chicago, Thay flew to Washington, D.C., where, in a June 1st press conference, he presented a five-point peace proposal for ending the war in Vietnam, including an immediate ceasefire and a schedule for U.S. troop withdrawal.

According to Chan Khong’s book Learning True Love (2007), the five-point proposal included the following:

“That same day, he was denounced on Saigon radio, in newspapers, and by the Thieu/Ky government as a traitor. From this point on, it was not safe for him to return to Vietnam. He decided to come home after his speaking tour anyway, at his own risk, but we in the SYSS begged him to wait.”

Denied the right to return to Vietnam, he began an exile that would last almost four decades. “Because,” Thay later said, “I had dared to call for peace.”

A week after being labeled a traitor to Vietnam, Thay’s powerful peace poetry was featured on the front page of the New York Review of Books. The same night, a special event on “Vietnam and the American Conscience” was organized for him at the New York Town Hall, featuring the playwright Arthur Miller, the poet Robert Lowell, and Father Daniel Berrigan — all outspoken critics of the war. On 25 June, 1966, Thay appeared in the “Talk of the Town” pages of The New Yorker.

The desperation of war had effectively catapulted him from the refuge of traditional monastic training in Vietnam to the forefront of the American political and intellectual scene of the ’60s.

Father Thomas Merton wrote the foreword for the English edition of Thay’s 1967 book Lotus in a Sea of Fire, which was published in the U.S. that same year by Hill & Wang in America. (Vietnamese edition: Nhất Hạnh, Hoa Sen Trong Biển Lửa). The book made an eloquent, hard-hitting, insightful, and rational plea to end the violence. It was printed underground in Vietnam, ran to multiple editions, and sold tens of thousands of copies.

The Fellowship of Reconciliation organized for Thay to continue speaking out for peace in Europe. He had two audiences with Pope Paul VI, whom he invited to visit Vietnam. According to the Fellowship of Reconciliation archives, “Thich Nhat Hanh: A Brief Biography,” (1970), held in the F.O.R. archives at Swarthmore, ‘The subsequent trips to North and South Vietnam by Archbishop Pignedoli and Msgr. Huessler have been linked by Vatican journalists to Nhat Hanh’s suggestion.”

Thay held press conferences in Copenhagen, Paris, Rome, Geneva, Amsterdam, and Brussels. He spoke about the situation in Vietnam at universities and churches, often to audiences of over a thousand people. He spoke at the parliaments of the UK, Canada, and Sweden, and met the philosopher Bertrand Russell in the UK. In Canada, Thay was the first non-Canadian to be invited to speak before the Canadian Parliament’s Committee of External Affairs.

Per Thay’s private unpublished papers, in Holland he befriended the World War II resistance fighter Hebe Kohlbrugge and the theologian Hannes de Graaf, and in Germany the Lutheran Pastor Reverend Heinz Kloppenburg, and Martin Niemöller, theologian and opponent of the Nazis — all of whom became loyal friends and associates in Europe. In the autumn, Thay’s tour calling for peace continued on to Australia, New Zealand, the Philippines, and Japan.

As he was traveling from city to city to call for peace, Thay received word of tragedies in his community in Vietnam. Shortly after Thay left, the SYSS campus was attacked with grenades; and again on 24 April 1967 (per his unpublished private papers), killing a student social worker and visiting professor, and injuring sixteen others.

Thay was in Paris in May of that year when he received the devastating news that his student Nhat Chi Mai, one of his first six disciples to ordain in the new Order of Interbeing, had immolated herself. On 14 June 1967, five of his young SYSS social workers had been led to the bank of the Binh Phuoc River by armed men and shot. One fell into the water and survived; the other four died immediately.

The attack is recounted in Sisten Chan Khong’s book, Learning True Love (Rev. 2007).

Upon hearing the news about the young SYSS social workers, Thay cried. A friend comforted him, saying, “Thay, there’s no need to cry. You are a general leading an army of nonviolent soldiers. It is natural that you suffer casualties.” Thay replied, “No, I am not a general. I am just a human being. It is I who summoned them for service, and now they have lost their lives. I need to cry.”

The tragedy marked Thay and led him to dig ever deeper to discover the roots of hatred and violence, which he found to be in wrong perceptions. Thay said, “We must use the sword of understanding to put an end to all views we have about each other; all notions and labels. All these labels must be cut off. Views can lead us to fanaticism. They can destroy human beings. They can destroy love.”

- Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.“His ideas for peace, if applied, would build a monument to ecumenism, to world brotherhood, to humanity.”

In January 1967, six months after they first met, Dr. King nominated Thay for the Nobel Peace Prize, saying, “His ideas for peace, if applied, would build a monument to ecumenism, to world brotherhood, to humanity.” See full text of the nomination letter.

A few months later, on 4 April, 1967, Dr. King quoted Thay’s book Lotus in a Sea of Fire in his landmark “Beyond Vietnam” speech at the Riverside Church in New York. It was the first time he unequivocally denounced the war and finally united the peace and civil rights movements. Dr. King shared Thay’s powerful message that “Men are not our enemy. Our enemy is hatred, discrimination, fanaticism, and violence.” And when Dr. King marched against the war, he marched under banners with these words in Vietnamese as well as English — for example, on 25 March, 1967 while leading a march against the Vietnam war in Chicago.

Thay and Dr. King met for the second (and last) time in May 1967 in Geneva, at the Pacem in Terris (II) Conference organized by the World Council of Churches. Their discussions centered in particular on their shared global vision of a ‘beloved community,’ a fellowship among peoples and nations built on principles of nonviolence, reconciliation, justice, tolerance, and inclusiveness in which even enemies can become friends.

Thay and Dr. King’s vision was not a utopian one, but a realistic, achievable goal attained when a critical mass of people can be trained in the principles and practices of peace and nonviolence.

Less than a year later, Dr. King was assassinated. Thay was in the U.S. when he heard the tragic news. Their friendship, shared courage and vision, and then the loss, had a profound impact on him. “I was devastated,” he later said. “I could not eat. I could not sleep. I made a deep vow to continue building what he called ‘the beloved community,’ not only for myself but for him also. I have done what I promised to Martin Luther King, Jr. And I think that I have always felt his support.”

Thay’s relentless itinerary brought him — via Hong Kong and India — back to Paris, where he continued his peace work at the Paris Peace Talks (1968-73), officially representing Vietnam’s Buddhist Peace Delegation. He was nominated to this role by Vietnam’s Unified Buddhist Congregation.

Together with volunteers and friends who came to assist, they rented a small apartment in a poor Arab neighborhood in Paris. In addition to their peace activism, they continued their efforts to support relief operations in Vietnam, and soon began to sponsor thousands of children orphaned by the violence. By 1975, 20,000 donors in Europe and the U.S. were supporting more than 10,000 orphans back in Vietnam.

Note: Details in this section are drawn from Sisten Chan Khong’s book, Learning True Love (2007).

Working long days, Thay guided the small community in Paris to incorporate mindfulness and compassion in every action: whether making phone calls, drafting documents, writing letters, eating meals together, or simply washing dishes. The days would end with songs and silent sitting meditation.

On the weekends, Thay organized public sessions of meditation and mindfulness at a nearby Quaker meeting house, attracting many young seekers. It was during this time that he deepened his friendships and dialogue with other faith leaders, in particular Christian priests and pastors, later leading to a series of powerful books on Buddhist-Christian dialogue. Jesuit priest and pacifist Father Daniel Berrigan even came to live with him for several months to learn meditation.

Father Daniel Berrigan arrived in September 1974. Their remarkable late-night conversations in the offices in Sceaux were recorded and published with the title The Raft Is Not the Shore: conversations toward a Buddhist-Christian awareness (Beacon Press, 1975).

Information in this section is drawn from Thay’s books Living Buddha, Living Christ (1995), and Going Home: Jesus and Buddha as Brothers (1999).

While in Paris, Thay began teaching Buddhism at the prestigious Sorbonne École Pratique des Hautes Études. As a professor he had access to the extensive Buddhist manuscript collections at the National Library. There, he discovered rare documents detailing the life of Master Tang Hoi, a monk of Vietnamese-Indian heritage in the 3rd Century, who became the first Zen Master in China, three centuries before Bodhidharma. Thay’s research was captured for Western readers in his book Zen Keys, first published in 1972 in French as Les Clés Pour le Zen, and later in his book, Master Tang Hoi: First Zen Teacher in Vietnam and China (2001).

Master Tang Hoi practiced and taught Zen, and was a pioneer in the Mahāyāna tradition, drawing on the meditation texts of early Buddhism, including those emphasising conscious breathing and mindfulness (the Satipaṭṭhāna and Ānāpānasati sutras). Discovering the writings of such an important early Vietnamese Zen master was a deep source of inspiration, and laid a path for the kind of Zen Thay would develop and teach in the West.

Thay’s public activism was not restricted only to Buddhism and peace. Together with Alfred Hassler (of the Fellowship of Reconciliation) and other leading intellectuals and scientists, Thay helped convene Europe’s first conference on the environment, in Menton, France. Their actions began with the Menton Statement, published in the UNESCO periodical Courier — “A Message to our 3.5 billion neighbours on Planet Earth” (which addressed environmental destruction, pollution, and population growth) was signed by over 2,000 scientists.

Thay and his associates met with U.N. Secretary-General U Thant the following year to engage his support, and in 1972 hosted the “Dai Dong” Environmental Conference alongside the U.N. Summit on the Human Environment in Stockholm.

Per Chan Khong’s book, Learning True Love (2007), while in Stockholm, Cao Ngoc Phuong had an energetic series of side meetings with government agencies and ministers, and succeeded in persuading them to sponsor the SYSS/Unified Buddhist Church social work programs to rebuild bombed villages in Vietnam. The first grant, made through the Swedish Lutheran Church, was for US$300,000.

Deep ecology, interbeing, and the importance of protecting the Earth continued to evolve as a powerful theme in Thay’s teachings, ethics, and writings.

In 1975 Thay finished the manuscript for The Miracle of Mindfulness. Written originally as a manual for his social workers back in Vietnam, to give them the spiritual strength they needed to continue their work without burning out, it rapidly became a leading meditation manual in the West.

From University of Oxford’s Prof. Mark Williams’ new foreword to Thich Nhat Hanh, The Miracle of Mindfulness (Gift Edition, 2015):

It was, as Jon Kabat-Zinn later said, “The first book to awaken a mainstream readership to the subject of mindfulness.” It broke new ground in the meditation scene of the late 1970s and early ’80s, taking meditation out of the meditation hall, and revealing how mindfulness could be integrated in everyday life. As an Oxford University academic has said, “It quietly sowed the seeds of a revolution.”

Today it has become a bestselling meditation classic published in over 30 languages.

The Miracle of Mindfulness was first published by the Fellowship of Reconciliation in the U.S. in 1974 with the title The Miracle of Being Awake. Only after it was accepted for publication by Beacon Press in 1975 did it receive its present title The Miracle of Mindfulness. It was also published by Pax Christi in London with the title Be Still and Know: Meditation for Peacemakers. It was first published in French with the title, Le Miracle est de Marcher sur Terre (“The Miracle Is to Walk on Earth”). It was published in 1976 in Sri Lanka and Thailand as “a manual on meditation for the use of young activists.”

Growing Global Mindfulness

Keep reading to discover more of Thay’s story as he pioneers and extends mindfulness communities, deepens the concept of interbeing, and comes to connect mindfulness and suffering with environmental activism.

Turn Your Inbox into a Dharma Door

Subscribe to our Coyote Tracks newsletter on Substack to receive event announcements, writing, art, music, and meditations from Deer Park monastics.