DOING THE WORK

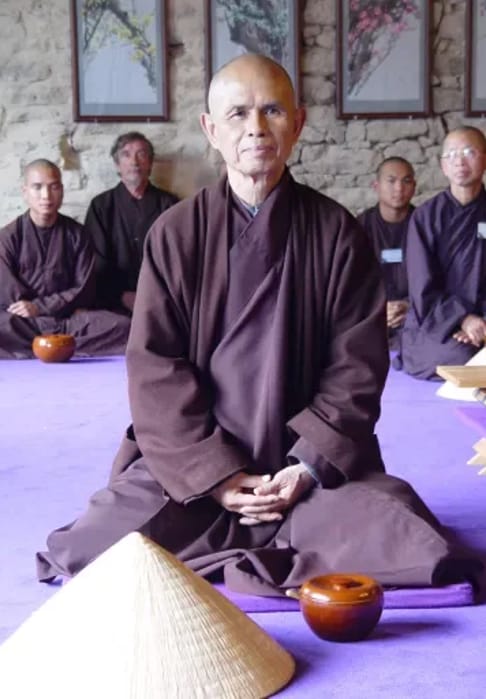

“It’s not enough just to talk about compassion; we have to do the work of compassion.”

- Thich Nhat Hanh

“It’s not enough just to talk about compassion; we have to do the work of compassion.”

- Thich Nhat Hanh

In December 1976, Thay attended the World Conference on Religion and Peace in Singapore. There, he learned of the plight of people beginning to flee former South Vietnam by boat. Already thousands were adrift on the open seas, at the mercy of storms and pirates. When boats did make it to shore, they were often pushed back out. Unable to lead his community’s social work programs back in Vietnam, Thay could still help the boat people. “It’s not enough just to talk about compassion; we have to do the work of compassion,” he later said.

From Singapore, Thay, Phuong, and their associates rented two large boats, the Roland, a cargo ship, and the Leap Dal, an oil tanker, as well as a small airplane to search the water. Within a few weeks, they had rescued over eight hundred people from the high seas.

But the rescue efforts angered the U.N.’s High Commissioner for Refugees, and after three months the program was shut down. The rescue boats carrying hundreds of people were not allowed to enter Malaysian waters to find shelter from a threatening storm, nor were they allowed to be resupplied with food or fuel. Thay was given 24 hours to leave Singapore.

This setback was a moment of immense pressure and despair, with hundreds of lives depending on his actions. Thay turned to meditation to find a way out, and practiced meditation through the night. He later said that it was only through concentrating on his breath and steps, that he was able to re-establish peace and clarity, and get the insight he needed to find a solution: to overturn his deportation, so he could stay longer in Singapore, and have time to arrange matters to guarantee the safety of everyone on their boats.

Thay realised that if he could persuade the French Ambassador to intervene on his behalf, and persuade the Singaporean authorities to let him stay another week, he would have enough time to make arrangements to secure the safety of the hundreds of refugees out at sea on their boats without fuel or food.

His experience in Singapore proved to him that in even the most difficult situations, with mindful breathing, peace, clarity, and insight are always possible.

Details on this time period in Thay’s life are drawn from his books At Home in the World (2016) and The Sun My Heart (1982).

In June 1982, Thay was in New York and participated in a peace demonstration while teaching a retreat for a number of students of the late Japanese Zen Buddhist monk Shunryu Suzuki.

Thay led the delegation to walk slowly, in peace, but their pace was too slow for the crowd behind them, many of whom became angry as they overtook the group. “There’s a lot of anger in the peace movement,” he observed. And so Thay’s focus shifted from demonstrations and press conferences to the deeper work of transforming consciousness through mindfulness retreats and community living.

“Even if we were able to transport all the bombs to the moon, we’d still be unsafe, because the roots of war and bombs are still there in our collective consciousness,” he said. “We cannot abolish war with angry demonstrations. Transforming our collective consciousness is the only way to uproot it.”

According to The New York Times, the nuclear disarmament rally on nuclear disarmament rally in New York City on June 13, 1982 was one of the largest peace rallies in U.S. history. Thay was in New York for a “Reverence for Life Conference”, an interfaith conference on nuclear disarmament being held alongside a summit of world leaders, “The United Nations Second Special Session on Disarmament.”

Elements of this story come from Thich Nhat Hanh’s, 21 February 1991 Dharma Talk.

From his active involvement in Vietnam in the fifties and sixties, to his time in Paris in the ’70s, Thay had come to see the creation of physical environments of peace and communities of mindful living as the surest way to heal the wounds of war and suffering and to cultivate the seeds of peace, healing, reconciliation and awakening in the world.

In Paris, Thay and his colleagues had begun to spend time at a farmhouse near the Foret d’Othe, where they retreated at weekends. They called it “Sweet Potatoes,” and there, as in Phuong Boi in Vietnam’s Central Highlands, Thay saw the healing potential of exploring the art of mindful living, as a community, close to nature.

In 1982 Thay and his followers found an old farm and land in the Dordogne Valley of southwest France. There, amid rolling hills and vineyards, they established a mindfulness practice center, which became known as Plum Village, after the 1,250 plum trees they soon planted in the rich soil. The existing Plum Village buildings were dilapidated, and the set-up was rustic. Barns became meditation halls and sheep-sheds became dorms, with beds made of wooden boards balanced on bricks.

Over the next two decades, Plum Village would grow into the largest Buddhist retreat center in the west, attracting people from around the world, with over 4,000 retreatants every summer and more than 10,000 visitors every year.

In the 1980s and 90s, Thay visited the U.S. frequently and had a growing influence on the burgeoning Western meditation scene, leading retreats at new Buddhist meditation centers on both East and West Coasts — including the Insight Meditation Society, Omega Institute, Ojai Foundation, and the San Francisco Zen Center.

The model of an immersive mindfulness retreat he designed and offered was radically distinct from the formal sesshin (sitting meditation) retreats being offered by Japanese Zen traditions in the West; the pujas (ceremonial retreats) offered by Tibetan Buddhists, or the silent retreats offered in Theravada traditions. Thay developed a retreat program that incorporated a new style of guided sitting meditation, his new form of relaxed outdoor walking meditation, a more intimate and less formalised practice of eating meditation, guided lying-down relaxations, small discussion groups, tea meditation, “service meditation” (working in the garden, cleaning the bathrooms or washing pots), and guided instructions for deep prostrations (a practice known as “Touching the Earth”).

Thay drew on his strong foundation in Buddhist psychology and understanding of Western culture to develop uniquely Buddhist practices for compassionate communication and reconciliation. All these practices, developed by Thay himself in Plum Village in France, created a powerful new model for mindfulness retreats that has today been popularised around the world.

Thay emphasised the importance of the Buddhist ethical code and Five Precepts in meditation practice, which many people were leaving aside, asserting that they were inappropriate for a modern Buddhism in the West.

Thay insisted that ethics and mindfulness could not be separated and that meditation or mindfulness without ethics is not true mindfulness. Thay’s retreats during the 1980s were attended by many practitioners who have since become leading mindfulness teachers in the West, including Joan Halifax, Jack Kornfield, Joanna Macy, Sharon Salzberg and Jon Kabat-Zinn. Thay’s teachings on ‘everyday mindfulness’ and his style of walking meditation have now been taken up and popularised by the secular ‘mindfulness movement’ and brought healing to millions around the world.

Some information from this section is drawn from James William Coleman’s book The New Buddhism: The Western Transformation of an Ancient Tradition (2002)

It was during one of Thay’s retreats at Tassajara Zen Center in California that he coined the word “interbeing” to describe the way in which everything “inter-is” with everything else.

Using the root verb “to be” like this was a powerful new way to translate sahabhūtā or pratītyasamutpāda (Skt.) sometimes explained as “interdependent co-arising.”

From Thich Nhat Hanh’s 1 October, 2013 Dharma Talk in Plum Village (translated from Vietnamese), “We have to inter-be. We use the word interbeing in order to free ourselves from the idea of being. We say we inter-are to free ourselves from the idea that we can be by ourselves alone. As soon as we are free of the idea of being we are free from the idea of non-being. Thanks to the idea of interbeing we are free from both being and non-being. That is thanks to the skill of the “wisdom of adaptation.”

We may still use words and concepts but we use them very skilfully to gradually free ourselves from words and concepts. We make use of new notions like co-arising and interbeing in order to free ourselves from old notions like birth and death, being and non-being. Once we are free from these ideas we can then also let go of the notions interbeing and co-arising — just like when we use a spade to dig a well, once we have dug the well we put the spade down. We do not need to carry it around with us everywhere. While co-arising and interbeing help us transcend birth, death, being and non-being, they are not an ultimate truth to be held on to forever.”

Thay taught his students to look with “the eyes of interbeing” to see that there cannot be a sheet of paper without clouds, forest and rain; there cannot be a mother or father without daughter or son. “Everything coexists,” he explained. “To be is to inter-be. You cannot just be by yourself alone; you have to inter-be with every other thing.”

In his early retreats, Thay went on to teach that you cannot have happiness without suffering, the mud without the lotus. The ‘insight of interbeing’ became central to his teachings on communication, ecology, conflict-resolution, political division, and even personal family relationships. The word ‘interbeing’ although it still uses words and the idea of ‘being’ is a skillful way to go beyond dualistic ideas of separation to touch the true nature of reality. Interbeing became one of Thay’s most distinctive contributions to Buddhist teaching.

In 1984 Thay’s father passed away in Nha Trang, Vietnam. He could not return for the funeral. Thay practiced deeply to see his father’s continuation in him: “My father is there in every cell of my body,” he said in one of his talks. “My mother also. My grandfathers, my grandmothers, my ancestors, they have not died; they are fully present in every cell of my body. When I hear the bell, I invite all of them to join me in listening. As we hear the bell, we can say silently: We listen, we listen. This wonderful sound brings us back to our true home.”

The information in this column is drawn fro Thay’s book The Other Shore (2016) and his 20 June, 2014 Dharma talk

Over the years, Thay embraced and healed the pain of not being able to return to Vietnam. It was, he explained, “...thanks to the practice I was able to find my true home in the here and the now. Your true home is not an abstract idea, it is a solid reality you can touch with your feet, with your hands, with your mind. It is available in the here and the now, and nobody can take it away. They can occupy your country, yes. They can put you in prison, yes. But they cannot take away your true home and your freedom.” He described the phrase, ‘I have arrived, I am home’ as the ‘cream’ of his practice and “the shortest teaching I can give.” He guided the hundreds (and later thousands) of people who began attending his retreats in Plum Village, to truly arrive and feel at home in themselves in the here and now.

In the early years of Plum Village in the 1980s, Thay devoted his time to continuing to research ancient sutras and publish new books and translations, bringing new life to classic texts and making them available to a wider audience. His translation of the Heart Sutra, the most important sutra in Mahayana Buddhism, soon became the authoritative modern English translation; while his Buddhist primer, The Heart of the Buddha’s Teachings, remains a classic textbook.

Equipped with mastery of both classical Chinese, Pali and English, he produced modern translations of the Ānāpānasati Sutta, the Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta, and the Diamond Sutra, transforming them from obscure texts into practical manuals of meditation and contemplation that were both applicable and relevant. His seminal biography of the Buddha, Old Path White Clouds is a bestseller published in over twenty languages — with its lyrical language and accessible Buddhist teachings and told without miraculous embellishments, successfully established the Buddha as a human being, not a god.

Elements of this section are drawn from Thay’s book The Heart of Understanding (1987) and his Buddhist Lectures.

Although Thay succeeded in making Buddhism accessible to western audiences, he maintained that Buddhism should never be diluted. Even his most deceptively simple messages were rooted in his scholarship and research of the Chinese and Pali canons, and his deep grasp of Buddhist psychology. Many of his scholarly teachings and courses were given in Vietnamese to his community in Plum Village, and await translation into English.

In 1988, after over thirty-five years of teaching, Thay finally began to ordain his own monastic disciples and establish a monastic community. That November — on Vulture Peak in India — Thay ordained his long-time student and collaborator Phuong (Sister Chan Khong, “True Emptiness”), together with others, including Annabel Laity (Sister Chan Duc, “True Virtue”), who became his first Western monastic disciple.

Thay came to value the importance of the teacher-student relationship — making a lifetime commitment to study and practice together without interruption in the context of a residential community of mindful living. By the mid-1990s, there were about thirty monks, nuns, and lay disciples from half a dozen nationalities living and training with him in Plum Village. As the community evolved, so did his teachings on spiritual practice in community.

Thay pioneered greater equality between nuns and monks, and emphasised decision-making by consensus rather than by authority, becoming the first Buddhist master from the East to combine seniority and democracy in the governance of the monastic community. He made the revolutionary step of revising the monastic vows (Pratimokṣa) for Bhikkhus and Bhikkhunis (monks and nuns).

Thay presented his revised monastic code at Choong Ang Sangha University in Seoul, Korea, on March 31, 2003. His new liturgy, published in 1989, was the first Vietnamese Buddhist daily chanting text to be written in vernacular Vietnamese rather than classical Chinese. The Vietnamese edition was printed as Nghi thức Tụng niệm by La Boi Press California (1989) and the English edition as Chanting from the Heart: Buddhist Ceremonies and Daily Practices (1991).

Elements of this section are drawn from Thay’s books Joyfully Together: The Art of Building a Harmonious Community (2003) and Freedom Wherever We Go: A Buddhist Monastic Code for the 21st Century (2001).

For more about women in the Plum Village Tradition, see: “Female Buddhas: A Revolution for Nuns in the Plum Village Tradition,”

Thay was one of the first modern meditation teachers to remove the mystique of Zen, and make the practice of going home and touching the present moment truly accessible.

Thay developed concrete methods of mindfulness practice including clear training in the art of mindful breathing, mindful walking, mindful dish-washing, teeth-brushing, cooking, or working, and the art of complete stopping and listening whenever the temple bell (or telephone) rang.

In response to a growing demand to attend retreats with Thay, in the late 1990s, the community opened additional monastic-led mindfulness practice centers in the U.S., in Vermont (Green Mountain Dharma Center); and California (Deer Park Monastery). Thay also ordained dozens of senior lay students to become Dharma Teachers continuing his work and teaching out in the world. Many of them started mindfulness communities in Europe, America, and Australasia, and have become distinguished teachers in their own right.

Thay emphasised the power of collective meditation practice for healing and transformation — and the importance of building local mindfulness groups (or ‘sanghas’) to offer companionship, joy, and solidarity, and address the loneliness, alienation, and individualism prevailing in the modern world.

Today, his lay students have established a network of over 1,500 mindfulness communities in more than forty countries. And Thay went on to found nine further monastic practice centers: Blue Cliff Monastery in upstate New York; Maison de l’Inspir in Paris; Healing Spring Monastery in Verdelot, France; the European Institute of Applied Buddhism in Germany; Thai Plum Village Practice Center in Khao Yai, Thailand; Magnolia Grove Monastery in Mississippi; the Asian Institute of Applied Buddhism (AIAB) on Lantau Island, Hong Kong; Stream Entering Monastery in Porcupine Ridge, Australia; and Mountain Spring Monastery in Bilpin, Australia.

The nineties and early 2000s saw Thay bringing Buddhist practices and teachings out of their primarily religious context to be of service to the world, as he led special retreats for psychotherapists, teachers, business leaders, politicians, scientists, environmentalists, artists, police officers, and even for Israelis and Palestinians.

In the U.S., he led retreats for American war veterans—the very people who had been sent to attack his homeland—to deepen reconciliation between all sides.

Thay’s teachings for businesspeople and political leaders can be found in his book The Art of Power (2007). His teachings for law enforcement officers and prisoners are published in Be Free Where You Are (2002). And his teachings for Israelis and Palestinians are published in Peace Begins Here: Palestinians and Israelis Listening to Each Other (2001).

Thay drafted a new universal code of ethics in the Buddhist tradition — The Five Mindfulness Trainings — which he presented at an international summit at the Indian Parliament in 1996; and at the White House and the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland in 2000.

It is estimated that over the last four decades, hundreds of thousands of people have made a formal commitment to apply these ethics in their daily life. In 1999, UNESCO invited Thay to join Nobel Peace Prize laureates in helping draft the “Manifesto 2000” for the new millennium, based on his text.

The manifesto gathered over 70 million signatures worldwide, including those of many heads of state.

Thay was invited to bring his teachings on applied ethics to China, in a series of trips at the turn of the millennium, as an official guest of the Buddhist Association of China. He was hosted by the deputy Minister for Religious Affairs, and received a large reception at leading Zen temples. There, he paid his respects to the patriarchs of his Zen lineage, and was invited to offer teachings and retreats.

Thay brought back to China a renewed Buddhism that was more relaxed, joyful, practical, and accessible; his books Anger, The Miracle of Mindfulness, and Old Path White Clouds have found popularity with a new generation of seekers. His new handbook for novice monastic training Stepping Into Freedom: An Introduction to Buddhist Monastic Training (1997) (Vietnamese: Bước Tới Thảnh Thơi (1996) became the first translation into modern Chinese in over 400 years and is read widely in Buddhist institutes.

In the early 2000’s, Thay became a leading Buddhist spokesperson for ‘deep ecology,’ developing his teachings on the environment that began with the Dai Dong conferences in the early 1970s. The insight of ‘interbeing’ became a foundation for his engaged action. He published The World We Have: A Buddhist Approach to Peace and Ecology (2008), fearlessly telling the truth, and outlining a Buddhist approach to the growing environmental crisis. “If the human race continues on its present course, the end of our civilization is coming sooner than we think,” he wrote.

In 2007 he led his entire community to become vegan, as a powerful message on how a plant-based diet can reduce suffering and protect the Earth. His Blue Cliff letter, “Sitting in the Autumn Breeze,” guided the entire residential community of all his practice centers to become vegan, to reduce not only animal suffering but also their carbon footprint.

His deepest insights for environment activists, captured in his book Love Letter to the Earth, are an invitation to “fall in love with the Earth,” to create a truly sustainable source of energy to inspire action and engagement.

In September 2001, Thay was in the U.S. leading retreats and giving public talks and interviews on his book, Anger, when the World Trade Center in New York was attacked. He led hundreds of people on walking meditation around Ground Zero and addressed the issues of non-violence and forgiveness in a memorable speech to over two thousand people at New York’s Riverside Church.

Six months into the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, Thay spoke boldly for peace at the U.S. Library of Congress, met with Senator John McCain to raise his concerns, and led a two-day mindfulness retreat for U.S. congressmen and congresswomen. He reaffirmed the importance of not demonizing the enemy and described compassion as a sign of great courage and strength — not of weakness — and the best way to guarantee true security and peace.

An Enduring Legacy

Please read the rest of Thay’s story as he is welcomed back to Vietnam, grows the Plum Village tradition around the world, faces health challenges, and inspires people everywhere to continue to build the beloved community he envisioned.

Turn Your Inbox into a Dharma Door

Subscribe to our Coyote Tracks newsletter on Substack to receive event announcements, writing, art, music, and meditations from Deer Park monastics.

Donations are our main source of support, so every offering is greatly appreciated. Your contribution helps us to keep the monastery open to receive guests throughout the year.